Infection

The deadly effects of the infection are the result of a potent toxin called CTX that the bacteria produce in the small intestine. CTX binds to the intestinal walls, where it interferes with the normal flow of sodium and chloride. This causes the body to secrete enormous amounts of water, leading to diarrhea and a rapid loss of fluids and salts (electrolytes).

About 75% of people infected with V. cholerae do not develop any symptoms, although the bacteria are present in their feces for 7-14 days after infection and are shed back into the environment, potentially infecting other people.

Approximately 5% of infected persons will have severe disease characterized by profuse watery diarrhea, vomiting, and leg cramps. In these people, rapid loss of body fluids leads to dehydration and shock. Without treatment, death can occur within hours.

Children are also more susceptible, with two to four year olds having the highest rates of infection. Individuals' susceptibility to cholera is also affected by their blood type, with those with type O blood being twice as likely to develop cholera as are people with other blood types. Persons with lowered immunity or children who are malnourished, are more likely to experience a severe case if they become infected.

The disease is not likely to spread directly from one person to another; therefore, casual contact with an infected person is not a risk for becoming ill.

Source

The most common sources of cholera infection are standing water and certain types of food, including seafood, raw fruits and vegetables, and grains. That have been contaminated by feces from a person infected with cholera

- Surface or well water. - Cholera bacteria can lie dormant in water for long periods, and contaminated public wells are frequent sources of large-scale cholera outbreaks. People living in crowded conditions without adequate sanitation are especially at risk of cholera.

- Seafood. - Eating raw or undercooked seafood, especially shellfish, that originates from certain locations can expose you to cholera bacteria. Most recent cases of cholera occurring in the United States have been traced to seafood from the Gulf of Mexico.

- Raw fruits and vegetables. - Raw, unpeeled fruits and vegetables are a frequent source of cholera infection in areas where cholera is endemic. In developing nations, uncomposted manure fertilizers or irrigation water containing raw sewage can contaminate produce in the field.

- Grains. - In regions where cholera is widespread, grains such as rice and millet that are contaminated after cooking and allowed to remain at room temperature for several hours become a medium for the growth of cholera bacteria.

Cholera bacteria also occurs naturally in coastal waters, where they attach to tiny crustaceans called copepods. The cholera bacteria travel with their hosts, spreading worldwide as the crustaceans follow their food source - certain types of algae and plankton that grow explosively when water temperatures rise. Algae growth is further fueled by the urea found in sewage and in agricultural runoff.

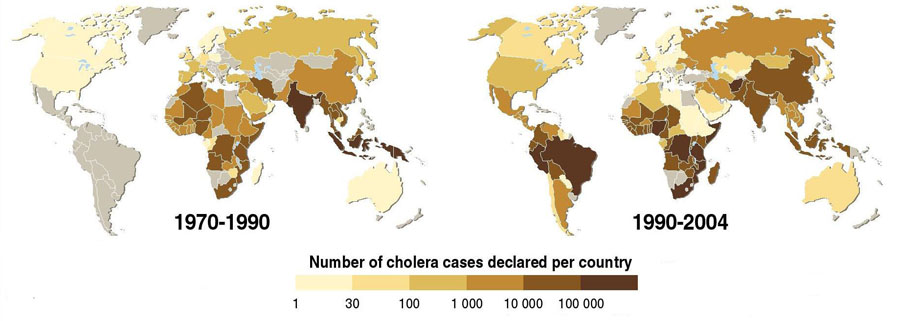

Cholera is a serious risk in the aftermath of emergencies, like the Haiti earthquake of 2010, but can be found and spread in places with inadequate water treatment, poor sanitation, and inadequate hygiene. The situation can be especially problematic in rainy seasons when houses and latrines flood and contaminated water collects in stagnant pools. Cholrea is a frequent companion of war and famine.

Cholera can be found around the world, in various regions including:

- Africa

- Asia

- India

- Mexico

- Central America

- South America

Symptoms

Most people exposed to the cholera bacterium (Vibrio cholerae) don't become ill and never know they've been infected. Yet because they shed cholera bacteria in their stool for seven to 14 days, they can still infect others through contaminated water. Most symptomatic cases of cholera cause mild or moderate diarrhea that's often hard to distinguish from diarrhea caused by other problems.

The primary symptoms of cholera are profuse diarrhea, nausea and vomiting of clear fluid. All of which left untreated will cause dehydration. Typically, symptoms of cholera appear within two to three days of infection. However, it can take anywhere from a few hours to five days or longer for symptoms to appear after ingestion of the bacteria.

- Diarrhea. - Cholera-related diarrhea comes on suddenly and may quickly cause dangerous fluid loss - as much as a quart an hour. Diarrhea due to cholera often has a pale, milky appearance that resembles water in which rice has been rinsed (rice-water stool) and may have a fishy odor.

- Nausea and vomiting. - Occurring especially in the early stages of cholera, vomiting may persist for hours at a time.

- Dehydration. Dehydration can develop within hours after the onset of cholera symptoms. Depending on how many body fluids have been lost, dehydration can range from mild to severe. A loss of 10 percent or more of total body weight indicates severe dehydration.

Dehydration may lead to a rapid loss of minerals in your blood (electrolytes) that maintain the balance of fluids in your body. This is called an electrolyte imbalance. An electrolyte imbalance can lead to serious signs and symptoms such as:

- Muscle cramps. - These result from the rapid loss of salts such as sodium, chloride and potassium.

- Shock. - This is one of the most serious complications of dehydration. It occurs when low blood volume causes a drop in blood pressure and a drop in the amount of oxygen in your body. If untreated, severe hypovolemic shock can cause death in a matter of minutes.

Complications

Cholera can quickly become fatal. In the most severe cases, the rapid loss of large amounts of fluids and electrolytes can lead to death within two to three hours. In less extreme situations, people who don't receive treatment may die of dehydration and shock hours to days after cholera symptoms first appear.

Although shock and severe dehydration are the most devastating complications of cholera, other problems can occur, such as:

- Low blood sugar (hypoglycemia). - Dangerously low levels of blood sugar (glucose) - the body's main energy source - may occur when people become too ill to eat. Children are at greatest risk of this complication, which can cause seizures, unconsciousness and even death.

- Low potassium levels (hypokalemia). - People with cholera lose large quantities of minerals, including potassium, in their stools. Very low potassium levels interfere with heart and nerve function and are life-threatening.

- Kidney (renal) failure. - When the kidneys lose their filtering ability, excess amounts of fluids, some electrolytes and wastes build up in your body - a potentially life-threatening condition. In people with cholera, kidney failure often accompanies shock.

Treatment

The goal of treatment is to replace fluid and electrolytes lost through diarrhea. Depending on your condition, you may be given fluids by mouth or by IV fluid. Antibiotics may shorten the time you feel ill. Antibiotics that may be used include tetracycline or doxycline.

Cholera can be simply and successfully treated by immediate replacement of the fluid and salts lost through diarrhea. The World Health Organization (WHO) has developed an oral rehydration solution to treat patients that is cheaper and easier to use than the typical IV fluid. It contains a prepackaged mixture of sugar and salts to be mixed with water and drunk in large amounts. Severe cases may still require intravenous fluid replacement. With prompt rehydration, less than 1% of cholera patients die.

Vaccination

A number of safe and effective oral vaccines for cholera are available. Dukoral, an orally administered, inactivated whole cell vaccine, has an overall efficacy of about 52% during the first year after being given and 62% in the second year, with minimal side effects.